Chapter One

Friday, April 12, 1861

USS Pawnee

Some miles from the Charleston rendezvous point

Passed Midshipman Gavin MacKenzie, United States Navy, ignored the salt spray pattering on his face as he stood watch on the ship’s raised quarterdeck. The gale had been blowing for several days and was only now—on the morning watch of 4:00 am to 8:00 am—moderating. The winds had diminished, but they were still strong. The seas were heavy, tumultuous, and unpredictable. The storm had delayed their departure from Norfolk and then slowed their progress as they steamed for the South Carolina coast. The ship would be a day late to the rendezvous.

Suddenly the stern rose sharply, and MacKenzie felt himself grow heavier. The vessel heeled to port. He grabbed for the starboard railing. In the predawn darkness he couldn’t see this particularly strong swell, but he wasn’t surprised when its crest broke over the railing and crashed into the back of his oilskin sou’wester hard enough to stagger him. “Son of a bitch,” he muttered. His head felt like he’d been hit with a hammer. The prolonged deluge made him feel like he was underwater.

The huge wave engulfed the quarterdeck, erupted over the skylight forward of the steering wheel, cascaded down to the gun deck, and exited the scuppers there.

MacKenzie had a good pair of sea legs, and he soon withdrew his hand from the railing as the ship righted itself. He shook his head. That blow might have given him a headache. “Damn,” he added.

He glanced over at the two helmsmen at the large steering wheel. One man had just gotten back up on one knee as he still held onto the spokes of the wheel. He quickly retook his station.

MacKenzie could see they were working hard to get the ship back on course quickly. They were good men, and he was confident he wouldn’t have to stand at their backs and hector them.

He checked out Midshipman Oliver Maxwell, who had been standing on the lee side of the quarterdeck. As officer-of-the-deck, MacKenzie was entitled to the weather deck, though in the contrary winds of the gale, it wasn’t easy to distinguish lee from weather. MacKenzie saw that Maxwell was holding on tight to the port railing and wiping salt water from his face. MacKenzie thought he looked okay.

MacKenzie wasn’t concerned about the Pawnee herself. Less than a year old, she had proven to be a good sea boat. He glanced upwards, idly. He couldn’t see very much. The Pawnee was carrying a few lights, one at the taffrail, two more at mastheads, and there was that dim light from the small, enclosed whale-oil lamps in the compass binnacle. The ship was running under a three-reefed spanker and a mizzen storm staysail. He wondered how long it would be before steamers like the Pawnee dispensed with sails entirely.

He glanced overboard, into the darkness. Not with fear but with respect. The power of the ocean always impressed him, fascinated him. That swell had lifted the 1,500-ton Pawnee as if it were a mere piece of driftwood. A man and his ship were puny compared to the sea.

And MacKenzie marveled that it was just water. In a glass, water was docile and transparent and colorless. But the oceans? They were powerful, invincible, unforgiving, demanding respect and obeisance, majestic, mighty, mysterious. And the seas could be blue, green, gray, black, red, brown—depending on weather and the skies but also on organisms and silt and even the sea bottom. Fascinating. He loved the sea.

He looked forward again. There wasn’t much to see. Given the weather, he had sent most of the watch below decks. If something untoward happened, of course, he would call them back up in a hurry. He could hear spray dancing on the decks and drumming off the smokestack. He could feel the slight vibration through his feet from the engines working steadily well below him, and he could hear—faintly above the wind—the reassuring clank and rumble of those same engines. But he saw no one moving about.

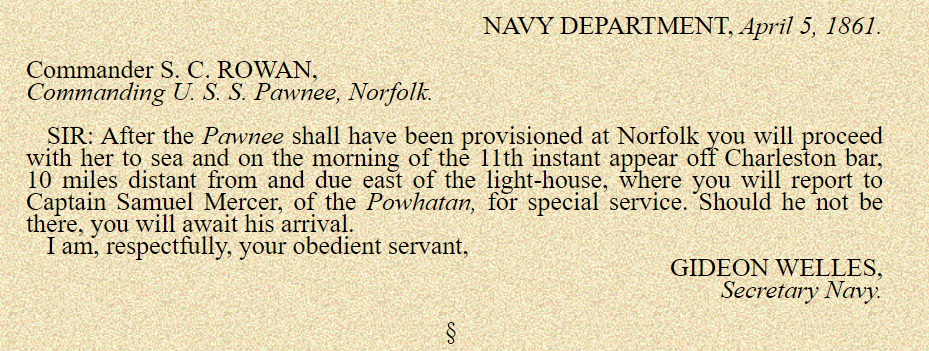

Ordinarily the morning watch was a bit boring anyway and gave a watch officer time to think. MacKenzie usually thought about women. But tonight was different. Tonight his thoughts were focused elsewhere. For the Pawnee’s captain, Commander Stephen Rowan, had read to all the officers his orders from Welles as soon as they had left Norfolk. The orders were short and vague but also ominous and significant. Charleston had to mean Fort Sumter. And Fort Sumter might mean war. And possible war absorbed a man’s thinking.

Midshipman Maxwell lurched up next to MacKenzie. “Sir,” the junior officer said.

MacKenzie turned and nodded. “Oliver,” he acknowledged.

Maxwell said, “I think it stopped raining, maybe a long time ago.”

MacKenzie said, “I agree. I’m tasting salt now on my face all the time. Nothing fresh about it anymore.”

MacKenzie liked Maxwell. They had shared one overlapping year at the Academy. Maxwell had graduated just the past year, 1860, three years after MacKenzie. He waited. “Yes?”

But Maxwell didn’t say anything. The midshipman glanced around as if looking for words. MacKenzie thought Maxwell’s issue really had nothing to do with the weather. The younger man did seem stressed though.

MacKenzie tried a different tack. He said, “Oliver, did you know that water covers seventy-five percent of the earth’s surface?”

Maxwell stared at him briefly. “Of course I know that,” he said, as if MacKenzie had asked a stupid question. “I’ve known that since I was a child.”

“Well, did you ever think about why?”

Maxwell guffawed. “No. I guess God wanted it that way?”

MacKenzie said, “Well, don’t you think it would have been more productive for Him to have reversed the proportions? Why so much water? Why not more land? And where did all the water come from?”

Maxwell chuckled. “Well, I’ll have to ask the good Lord about all that someday.”

“You do that, but don’t mention I questioned His judgment.” MacKenzie smiled.

Maxwell laughed. “Okay.” Then he shook his head as if to clear it. “Gavin,” he said, “what exactly do you suppose Welles meant by ‘special service’?”

MacKenzie sighed. “Ah, that again. Oliver, we’ve all been over this a dozen times.”

“Well, I just can’t stop thinking about it. It’s gotta be about Fort Sumter.”

“Seems reasonable. But we’ll just have to wait until we join Captain Mercer off the Charleston bar. He’ll tell us then.”

Maxwell nodded. Then he said, “I just couldn’t believe it when South Carolina seceded.” The state had made good its threat to secede if Lincoln were elected president. It had passed an ordinance of secession on December 20, 1860.

MacKenzie nodded. “Again, neither could I.”

“The country’s coming apart, Gavin. Seven states have seceded. Seven!”

“Yes,” MacKenzie said. Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana had all seceded by the end of January, and Texas had followed on February 1. “But none of the border slave states have seceded yet. Maybe they won’t.”

Maxwell said, “I was so shocked when Captain Hartstene resigned. He was the only captain the Pawnee had ever had up ‘til then.”

“You could see it coming,” MacKenzie said. Henry Hartstene, a South Carolinian, had resigned from the United States Navy on January 9, 1861. “I think we’ll be seeing many more Navy officers resigning their commissions.”

Maxwell said, “I had a lot of respect for Hartstene.”

“So did I,” MacKenzie said.

“But what he did was so dishonorable,” Maxwell said.

“Well,” MacKenzie said, “I give him credit for putting honor and duty first while he still held a United States commission. He delivered the Pawnee securely into Union possession before leaving. He made no attempt to snatch the ship for South Carolina.”

“Yes, but now Hartstene is in command of all the South Carolina naval forces in the Charleston area.”

“Yes.”

“Which is where we’re going.”

“Yes.”

“We might just wind up shooting at each other!”

“I hope it doesn’t come to that. But if there’s a war—”

Maxwell said, “If there’s a war? Why, the country came close to that back in January when the Rebels fired on the Star of the West. I’m glad she withdrew.”

The Buchanan administration had made a feeble, almost surreptitious attempt to resupply and reinforce Fort Sumter. The Army had leased a civilian steamer, the Star of the West, stuffed it with supplies and some soldiers, and sent it toward Charleston. But on January 9, the same day that the second slave state had seceded from the Union, the same day that Hartstene had resigned from the United States Navy, a battery on Morris Island had fired on the ship. Little damage was done, and no one was hurt. But the ship turned around and went back to New York.

MacKenzie said, “She was unarmed. You can’t blame her for aborting her attempt to reach Sumter.”

“Well, we aren’t unarmed,” Maxwell said.

MacKenzie said. “But we have neither supplies nor soldiers for the fort.”

“So what is our mission supposed to be at Charleston?”

MacKenzie shrugged. “I’m not sure. But Lincoln is not Buchanan. Lincoln is sending warships to Fort Sumter this time. I think he means for us to fight our way in—if that’s what we’re supposed to do.”

“So why didn’t Welles tell Rowan that in his orders?”

MacKenzie shrugged. “You’d have to ask Welles. Maybe Mercer is bringing updated orders.”

Maxwell said, “But the Rebels have now had months to build fortifications and batteries all around Charleston Harbor. We’ll be vastly outgunned.” Maxwell stretched out his arms in emphasis.

“We’ll have Mercer’s Powhatan,” MacKenzie pointed out.

The Powhatan was a more powerful warship than the Pawnee. She was a sidewheel steamer thirty feet longer than the screw-driven Pawnee and carried ten IX-inch Dahlgren smoothbore shell guns in broadside. The Pawnee was armed with the same type cannons, but she had only eight. And the Powhatan also had an XI-inch Dahlgren as a forward pivot gun. That monster weighed almost 16,000 pounds and could hurl a 135-pound shell over two miles.

“Well, I’m glad of that, sure,” Maxwell said. “But I don’t think it’ll make much difference.” He dropped his arms. It was a forlorn gesture.

MacKenzie had to agree, but he didn’t say as such.

Maxwell said, “And the Rebels know we’re coming, Gavin. There are no secrets in Washington.”

MacKenzie shook his head. “No. Welles must be bewildered over whom to trust even in his own department.”

“And if spies weren’t sufficient, the Confederates only have to read the northern newspapers. They regularly report on the Navy’s preparations and movements. It’s ridiculous.”

MacKenzie said, “I agree.”

Just then the ship heeled steeply to port, and another wave broke over the railing. MacKenzie, grabbing the railing again, was able to withstand the pounding, but Maxwell was swept off his feet to crash into the coaming of the skylight between the steering wheel and mizzen mast forward of it.

When the ship righted itself MacKenzie hurried over to Maxwell. “You okay?”

Maxwell lay on his back, grimacing. He grasped his right knee with both hands and rocked back and forth. He didn’t say anything.

“How bad is it?” MacKenzie asked, leaning over the fallen man.

Through gritted teeth Maxwell said, “It’ll pass. Just gimme a minute.”

MacKenzie straightened up but kept looking down at the man.

Finally Maxwell let go of his knee and rolled over. He struggled to get up.

MacKenzie helped him. “Can you stand?”

Maxwell nodded, but when he put weight on his right leg MacKenzie had to catch him to prevent him falling.

“Damn,” Maxwell muttered. Then he tried the leg again. This time he managed to stand. MacKenzie cautiously stepped away from him.

Maxwell said, “Thanks, Gavin.”

Now the deck tilted sharply to starboard. Maxwell blurted, “Shit!” Perforce, he hopped downhill on one leg until he clunked up against the quarterdeck bulwark. The ship righted itself. Maxwell smiled. “That wasn’t so bad.”

MacKenzie, who had slid to the railing again, smiled. He said, “If the deck had tilted in the other direction, you would have gone right through the skylight.”

“The captain wouldn’t have liked that,” Maxwell said.

MacKenzie smiled. “No,” he said. “So hang on to something all the time.”

Maxwell looked out into the darkness. “I fear greatly for the country, Gavin. What are we going to do?”

“Well, I don’t know about the rest of the country, but you and I will do our duty,” MacKenzie said.

“Of course, we will,” Maxwell said. “I didn’t mean to imply otherwise.”

“I didn’t think so,” MacKenzie said.

“Duty above all.”

“Yes,” MacKenzie agreed.

Maxwell seemed to have run out of talk.

“Mr. Maxwell,” MacKenzie said, slipping back into formality. “I’m going forward to check on the lookouts. You have the deck until I get back.”

Maxwell straightened up, but he kept a hand on the railing. “Aye, aye, sir.”

MacKenzie stepped up close to the binnacle in front of the wheel. He checked the compass. The course was correct. He looked at the quartermaster and nodded a compliment.

The man smiled a bit and nodded slightly in acknowledgement.

“Maintain that course, Boyd,” MacKenzie said.

“Aye, aye, sir,” the quartermaster answered.

MacKenzie also nodded to the man next to the quartermaster, who nodded back.

MacKenzie descended the three-step ladder to the gun deck and started slowly forward. He inspected the row of four massive, black, IX-inch Dahlgren smoothbore shell guns resting quietly in the darkness like sleeping giants. He glanced at the heavy breeching of the first gun. The cannon was safely secured just as it had been every other time he had checked the lashings during his watch.

He paused and spread his feet as the Pawnee rolled to starboard. He smiled. Ah, Poseidon, playing with us again, huh?

The ship quickly leveled herself again, and he started forward once more. He checked the breeching of the second gun with a glance, but then he stopped.

He hadn’t seen anything wrong. It was just that the guns were now far more significant than they had been: he might actually have to fire them at people he considered friends or at least fellow countrymen.

He put out a hand and rested it on the handle of the elevating screw of the nearest big gun. A cannon was simply an iron tube. But he had learned at the Academy that there was so much more to it than that. He knew that properly manned and fed with powder and a projectile, a cannon became like a living creature of massive destructive power.

MacKenzie smiled. His father had been an artillery officer in the Mexican War, but he had not fired anything more powerful than 12-pounder field artillery. The elder MacKenzie had never fired anything remotely like these magnificent Dahlgrens.

Commander John Dahlgren was an ordnance genius. This design of his was only five years old. The clever bottle shape of the gun gave the weapon extra strength at the breech end to withstand larger charges. And Dahlgren’s shell gun design allowed for firing solid shot as well as shells. And they could also fire shrapnel, canister, and grapeshot. A versatile, potent weapon.

Each gun weighed over 9,000 pounds. And at an elevation of 15 degrees it could hurl a 74-pound shell almost two miles.

Each Dahlgren gun sat on a massive Marsilly gun carriage. The carriage had forward trucks—small wheels—but only “dumb trucks” in the rear; the cheeks of the carriage rested directly on the deck. Friction between the carriage and the deck would limit recoil when the gun was fired. Running out and running in were facilitated by a roller-handspike placed under the rear edge of the carriage.

At the Academy MacKenzie had learned that cannons were actually complicated weapons. To begin with there was windage—the slight difference between the diameter of a projectile and the diameter of the tube. That slight difference provided allowance for variation in bore diameter, for variation in shot diameter, for any rough surface of a shot as well as rust, and for simply being able to roll the shot down the bore of the cannon. But windage could also refer to the deflection of a projectile because of wind, which had to be considered when aiming a cannon.

And there was more. Even though the explosion of the powder in a cartridge looked instantaneous to a human observer, it really wasn’t. Because the igniting flame reached the powder cartridge from the top through the vent above it, the powder burned downward through the cartridge. This meant that the top of a shot or shell was pushed down slightly as it started moving. This left a miniscule depression, called a lodgement, on the bottom of the cannon bore at the breech end. And the displaced metal formed a tiny burr in front of the projectile.

The shot bounced over this burr as it left the lodgement, but it was pushed back down by the expanding gases, which were rushing past the shot more on the top than on the bottom because of windage. The shot bounced several times in fact before it actually left the muzzle of the cannon. All these bounces caused enlargement, a series of depressions running down the bore of the cannon.

And the barrels could be cut and scratched by rough or broken projectiles. Each firing put a tiny bit of pressure on the inside of the cannon enlarging the bore. The vents of cast-iron cannons were particularly prone to enlargement through repeated use. And rust was the constant enemy of iron cannons.

All of these effects made the guns increasingly inaccurate with use. In fact, a cannon eventually became unserviceable in practice and had to be scrapped or simply tossed overboard.

And this didn’t even include consideration of the gunpowder used, which was worth a treatise of its own. Gunnery, MacKenzie had learned, was a complicated science.

MacKenzie glanced at the bulwark. It was about seven feet high and made of stout timber. Hammocks stowed in netting during the day made the bulwarks another foot higher. But they gave a false sense of security. The bulwark would protect the gun crews from small arms fire, but a solid shot would come right through, and a shell would explode the bulwark into huge, deadly, razor-sharp splinters.

MacKenzie detected movement above him. He glanced up and saw the starboard bridge lookout looking down at him, a telescope cradled in an arm. The bridge was the narrow walkway that stretched from the top of one bulwark to the top of the opposite bulwark, just forward of the ship’s huge smokestack and abaft the mainmast. A lifeline was provided by reeving lines through eyes on two rows of stanchions that stretched the length of the bridge, fore and aft.

MacKenzie snatched his hand away from the great gun, stood up straight, and gave the man a scowl. “Carter, are you supposed to be a lookout or a lookin?”

“Sir!” The seaman turned away quickly and pretended to study something out to sea through his telescope.

MacKenzie had to smile. He knew Carter couldn’t see a thing even though it was a night telescope. A night telescope had one lens less than a day telescope to let in more light. But that left the image inverted and backwards. MacKenzie hated night telescopes.

“See anything, Carter?” MacKenzie asked. He asked it partly to poke fun at the seaman but also to follow up his rebuke with a change of subject to show that that matter was closed.

“No, sir,” Carter answered.

“Still tethered to the lifeline?” MacKenzie didn’t think Carter was in danger of being swept overboard. But a rogue wave might reach the bridge and knock him off his feet. Falling to the deck from the bridge could break his neck. A short tether would break his fall just shy of the deck.

“Yes, sir.”

“Very well. Carry on.”

“Aye, aye, sir.”

MacKenzie started forward again, walking slowly. He went past the smokestack. A glance upwards showed sparks whipping away from its top. With this strong wind there would be no trouble maintaining a good draft for the boiler fireboxes.

And on a night like this, steam power was very welcome. It would have been a rough, challenging night if the Pawnee had had to rely on just sails. And where would the ship have been once the gale had blown itself out. But with steam they could maintain an approximate course despite the wind and seas.

But he didn’t think a steamer would ever match a pure sailing vessel for beauty. It would always be easier to love a beautiful, graceful sailing ship like, say, the USS Cumberland. The Cumberland and the Pawnee had both been part of the Home Squadron when the squadron had visited Mexico in the fall. He never tired of watching the Cumberland under sail.

Now, the Pawnee did have some graceful lines to her. And she did have a full set of sails that were very attractive to MacKenzie when set. And he loved to listen to the crackle and slap and rustle of canvas when the sails were worked or when the wind tussled them. But the smokestack ruined everything. Sort of like a beautiful woman having a large wart on the tip of her nose.

MacKenzie walked under the bridge and beyond it, then stopped once he had passed the last Dahlgren. He looked back at the cannon battery again. Would the first time he fired a cannon in earnest be a shot at what he still considered his own country? How could one fort have become so important?

For Fort Sumter was both unimportant and all important. The fort had been under construction for years and years and still wasn’t finished. At present there were fewer than two hundred men manning the fort, far below what was considered a full garrison. The men had been moved to Fort Sumter on its island from Fort Moultrie on the mainland near the end of December. The commander of all the forts in Charleston, Major Robert Anderson, knew he couldn’t possibly defend all the forts with his small force. And he knew the nascent Confederacy wanted possession of all the forts at Charleston. And in every other port in their new nation, as they considered it.

A convention in Montgomery, Alabama had established the Confederate States of America on February 8, 1861. Jefferson Davis was inaugurated as its first president on February 18.

Lincoln was inaugurated as president of the United States on March 4. And all the while—and since then—the fate of Fort Sumter had been debated in the public, in the press, in the United States Congress, and in both the Buchanan and Lincoln administrations: Should Fort Sumter be resupplied and reinforced, or should it be handed over to the Confederacy? Could the fort be resupplied and reinforced if the Confederacy tried to stop it?

The Confederacy considered continued Union occupation of Fort Sumter as an affront to its sovereignty and a potential hazard to its security. And the longer the United States continued occupying the fort, the more exasperated and enraged the Confederacy became.

Conversely, the United States government didn’t recognize the Confederacy as a country and still considered South Carolina as a state in the Union, albeit in rebellion. So the United States government saw no reason to hand over the fort to the Confederacy.

The stalemate had been going on for four months, ever since South Carolina had seceded. The Confederacy had already occupied Fort Moultrie and the other batteries around the Charleston Harbor. It had charged Brigadier General Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard with either negotiating an evacuation of Fort Sumter or forcing its surrender. The Confederate government had set no deadline, but all reports indicated that the general was very busy strengthening the other Charleston Harbor forts and batteries and preparing to seize Fort Sumter.

Fort Sumter presented the United States with a serious dilemma. The fort, situated in the middle of Charleston Harbor, had been designed to coordinate with forts ashore to repel an invasion from the sea. It was not designed to withstand an attack from those very same shore batteries. And it lay within easy cannon range of those batteries. The current garrison of the fort was too small to repel a ground assault landed on the island on which the fort stood. And most pressing, the fort had few supplies.

Both sides had been tiptoeing around the issue, neither side wishing for an open armed conflict. But the longer time went on, the greater became the symbolism of the fort. And the longer time went on, the more urgent became the need to re-provision the fort if the United States did not intend to hand it over.

The political situation was murky. Some people thought that Confederate batteries firing on the Star of the West had been an act of war, that the first shot in a civil war had already been fired. Others thought that since the ship had not been a government vessel, it wasn’t an act of war, even if it was flying a United States flag. Furthermore, some thought the firing had been the decision of some local battery commander anyway, not that of any higher authority. And in general people didn’t want it to be an act of war. So, a conclusion about whether it was an act of war or not drifted into limbo.

The issue had now come to a head. Major Anderson had told Lincoln he would run out of supplies by the middle of April and would have to abandon the fort unless resupplied. Time was up. Lincoln had to decide between trying to resupply the fort or handing it over to the Confederates. He was leery of trying the former and loath to do the latter.

And MacKenzie thought the citizens of South Carolina were just itching for some blood. He thought they would even be disappointed if Major Anderson simply sailed away from Fort Sumter without a fight. They wanted to take it.

MacKenzie was not sanguine about the Powhatan and the Pawnee being able to fight their way past a gauntlet of Confederate shore batteries. He would really like to have had a few of the Navy’s much larger frigates present. But MacKenzie knew that the Pawnee and the Powhatan were probably about the only ships the Navy could come up with on short notice for this emergency mission.

MacKenzie shook his head. All this thinking about the terrible situation made him feel gloomy. How had the country wound up rushing into such an imminent catastrophe?

He continued forward until he reached the Pawnee’s bow. He ascended the few steps to the raised foredeck. The lookout there turned to look at him.

MacKenzie said, “Miller.”

“Sir,” the seaman acknowledged.

MacKenzie moved closer so he could see the lookout’s face in the darkness better, but, in fact, he could always recognize Miller from his shape. Miller was almost six inches shorter than MacKenzie but built solid. He reminded MacKenzie of a siege mortar. The man had a full beard almost a foot long. He kept it carefully groomed, but it looked bedraggled in the storm.

MacKenzie liked Miller. The man was twice MacKenzie’s age, and he had been at sea since he started as a powder monkey at the age of eight. Miller didn’t talk much, especially if there were more than a few people around. But when you did manage to get him talking, he had wonderful tales of his travels all over the world. It was a primary reason Miller loved the Navy; he had seen the world.

MacKenzie had always had a talent for drawing with a pencil, and he found Miller an interesting subject for sketches. He liked sketching life aboard ship anyway, but men like Miller made for colorful images, if the word colorful could be applied to carbon pencil drawings. Miller had kept one such sketch MacKenzie had made of him, and the sailor was inordinately proud of it.

The bow rose as a swell reached it. MacKenzie glanced ahead and thought Miller in the bow had as good a vantage as Carter on the bridge when the bow rose as high as it was doing. Both men leaned into the tilt.

The Pawnee’s bow plunged. MacKenzie flinched as spray hit him directly in the face.

Miller said, “The sea’s still lively tonight, sir.”

MacKenzie smiled. “Indeed, Miller.” He wiped a hand across his face. He checked to see that Miller was tethered to the lifeline the Pawnee erected at the bow during heavy weather.

Miller said, “Well, she should quiet down some by the time we get close to Charleston.”

MacKenzie almost snorted. No one had told the crew where they were going, but old salts like Miller were hard to keep uninformed.

Miller said, “Saw the Cape Romain light awhile back. I’d say Charleston’s about twenty miles ahead, sir, maybe three points off the starboard bow.”

MacKenzie nodded, impressed. He thought that was pretty accurate. They were not headed directly for Charleston but for a rendezvous point ten miles due east of the Charleston light. That lighthouse was on the southern end of Morris Island, which itself was on the southern side of Charleston Harbor. So once the ship was ten miles due east of the lighthouse, Charleston Harbor would be about directly abeam the Pawnee, eight points off the starboard bow.

He was not surprised that Miller could pick out landmarks like the Cape Romain lighthouse. The sailor had probably been up and down the entire United States coastline a dozen times in his decades at sea.

MacKenzie said, “Your sense of reckoning is very good, Miller.”

“Thank you, sir.” He sounded genuinely pleased at the compliment. “You think there’s gonna be a fight when we get there, sir?”

Ordinarily MacKenzie felt that a seaman would be told what he needed to know when he needed to know it. But men like Miller were the backbone of the enlisted Navy. They deserved respect and some accommodation. “Could be, Miller,” he said. Which wasn’t very informative.

Miller said, “Well, the boys are ready for a fight, sir, if one comes our way.”

“That’s good to know, Miller. But I hope there won’t be a fight.”

“No, sir.” He sounded disappointed.

MacKenzie wasn’t surprised that Miller knew about the situation at Fort Sumter. Everybody had been discussing it for months.

The ship’s bell rang four times; one of the ship’s boys had made a quick dash topside to announce the time. It was 6:00 am. MacKenzie was halfway through his watch.

To Miller he said, “We won’t be entering Charleston Harbor itself, Miller.”

“I wouldn’t think so, sir,” Miller said.

MacKenzie said, “We should be meeting the Powhatan off Charleston.”

“A fine ship, sir. I know her.”

“And maybe a transport or two, I would think.”

“I’ll keep a sharp eye out for ‘em, sir.”

MacKenzie knew he would. Miller didn’t have a telescope; only the bridge lookouts were given telescopes. But Miller’s distance vision was keen, even if he couldn’t read anything closer than three feet in front of his face without spectacles, which he usually refused to wear.

MacKenzie turned and headed down the steps. “Carry on, Miller.”

“Aye, aye, sir.”

MacKenzie returned to the quarterdeck. “Mr. Maxwell,” he said. “I have returned.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Go make sure the captain was awakened. He wants to be on deck well before we reach the Charleston light rendezvous.”

“Aye, aye, sir.” The junior officer headed for the officers’ companionway. MacKenzie noted that Maxwell limped badly.

MacKenzie faintly heard a boatswain’s whistle below decks. Followed by, “Up all hands. Stow hammocks!”

The day began early for the enlisted crew. They would roll out of their hammocks now, take them down from the hooks assigned to them on the berth deck, and parade up to the gun deck—in good weather—where the hammocks would be stowed in the nettings atop the bulwarks.

Then they would wash themselves and then clean ship, a boring chore universally hated by the men. Breakfast was at eight bells—8:00 am. It was coffee and hardtack biscuits. Other meals of the day were more appetizing, but at least the biscuits were filling.

And breakfast was preceded by a ration of grog, a gill—four ounces—of watered-down whiskey. MacKenzie knew some sailors stayed in the Navy just because of the twice-daily grog ration. Most of the discipline problems he had to deal with aboard ship involved alcohol in some way.

Maxwell returned and reported that Captain Rowan was already awake.

“Very well,” MacKenzie said.

Another officer joined MacKenzie on the quarterdeck. It was Lieutenant Samuel Marcy, the Pawnee’s executive officer.

“Lieutenant Marcy,” MacKenzie acknowledged. He knew Marcy had the watch after his, the forenoon watch from 8:00 am to noon, so his greeting was really a question. Was he being relieved early?

“Morning, Gavin,” Marcy said informally.

“Good morning, Sam,” MacKenzie said. If Marcy had intended to relieve him, he would have greeted him as Mr. MacKenzie. So Marcy was just visiting; MacKenzie was still officer-of-the-deck.

Marcy glanced about. “Gale’s blowing herself out.”

“Yes, sir,” MacKenzie said. “But she can still surprise you. Be ready to grab onto something.”

MacKenzie waited for Marcy to speak further, but the senior officer said nothing.

“Couldn’t sleep, Sam?” MacKenzie asked. Officers didn’t have to rise as early as enlisted men unless they were on watch.

“My mind’s been racing, Gavin,” Marcy said. “I admit that.”

MacKenzie said, “Well, mine, too.”

“Endless discussions in the wardroom don’t resolve anything.”

“No.”

“Never been in this situation before.”

“No.”

And MacKenzie knew Marcy had been in many situations. He was much older than MacKenzie. Marcy had started in the Navy as a midshipman in 1838, when MacKenzie was only three years old. Marcy had been a lieutenant since 1852. He had spent a total of thirteen years at sea.

Marcy had been MacKenzie’s navigation professor at the Naval Academy. He had been on the first faculty at the Naval Academy in 1845, and he had returned twice more after other assignments elsewhere. He had been a professor at the Naval Academy once more just before becoming the Pawnee’s executive officer.

Marcy said, “I can’t believe it’s come to this, Gavin. The situation is a powder keg, and Fort Sumter could be the spark to set it off.”

“Do you still think Mercer intends to try to resupply the fort?”

Marcy said, “If I know Mercer, yes, I think he will try. But it will be very risky. Beauregard’s been working like a beaver mounting more and heavier batteries all around the Charleston Harbor. I think there’s a good chance he’ll be able to reduce Fort Sumter with them, and sinking a few ships will be even easier.”

MacKenzie nodded. Marcy hadn’t changed his mind about Mercer’s probable intentions since the last time he had heard Marcy discoursing in the wardroom. “So, we may all sink in a blaze of glory?”

Marcy snorted. “Hmph, glory. I remember you cadets at the Academy talking about winning glory in naval combat, Gavin.”

MacKenzie smirked. He said, “And you didn’t when you were a young officer, Sam?”

Marcy smiled. “Okay, point taken. Yes, yes, so did I and my cohorts. It’s what we all train for, after all.”

“And I’ll bet you read the same Marryat novels as we did.”

Frederick Marryat had been a Royal Navy officer for 25 years before resigning and devoting himself to a writing career. He was famous for his partly-autobiographical sea stories full of naval adventure in the Napoleonic era. They were widely popular in the United States, especially in the American Navy.

Marcy laughed. He nodded vigorously. “Oh, yes,” he said. “I still have my copy of Mr. Midshipman Easy.”

“I have a copy of that one myself,” MacKenzie said.

Marcy said, “Indeed? Yet it came out shortly before I became a midshipman myself. Must have been about—oh—1836, I suppose.”

“Something interesting in that book that kind of relates to today,” MacKenzie said.

Marcy looked at him. “How so?”

“Well, Easy is the protagonist, of course, but Mesty, the escaped Negro slave, plays almost as big a role in the story. And slavery in America is certainly the focus of the issues these days.”

Marcy nodded slowly. “I do remember that.” He sighed. “But then that was the Royal Navy and they had the French to fight.”

“Your point?”

“We may be fighting fellow Americans.”

MacKenzie said, “Yes. We weren’t trained at the Academy to fight a civil war, Sam.”

“No. The principles are much the same, of course. Warfare is warfare. But it’s hard to summon up an eagerness and the energy for combat in a civil war. It’s easier when you can hate the enemy, when they don’t look like you, when they speak a different language, when they come from a different part of the globe.”

MacKenzie said, “I don’t hate anybody in the South. Just the opposite.”

Marcy nodded. “Exactly. I have friends in the South, some in the Navy. Why, Captain Rowan’s wife is from Virginia.”

“From Norfolk,” MacKenzie said. “A Navy town for sure. I have many friends there myself.”

Marcy nodded vigorously. “As do I.”

MacKenzie added, “My best friend is from North Carolina. Elizabeth City.”

“Ah, yes. Jeremy Franklin,” Marcy said. “I remember him well. You two sure got into some—adventures.” Marcy smiled.

MacKenzie got a big grin on his face. He said, “That’s a tactful way of putting it, Sam.”

“Have your paths crossed since you both graduated?”

“Yes, indeed. In fact, I spent several days with Jeremy and his family this last August.”

“Good times?”

“Oh, yes, Sam. Very good times. Especially the day of the garden party. That whole day was memorable.”